“I conceive that the great part of the miseries of mankind are brought upon them by false estimates they have made of the value of things.” – Benjamin Franklin

Expensive On Other Planets: In Salt Lake City, I once met an exobiologist who studied the bacteria that live under the Antarctic ice-sheet. Camping in a tent, she spent her days diving into holes in frozen lakes to collect samples. She told me it was a “Mars model,” considered one of the few places on earth that can approximate extraterrestrial conditions.

Expensive On Other Planets: In Salt Lake City, I once met an exobiologist who studied the bacteria that live under the Antarctic ice-sheet. Camping in a tent, she spent her days diving into holes in frozen lakes to collect samples. She told me it was a “Mars model,” considered one of the few places on earth that can approximate extraterrestrial conditions.

NASA’s latest mission just spent $2.5 billion dollars to actually look for water on Mars. Its simple presence is a signal that life can exist, whatever planet you are on. Whether or not one feels this is money well spent, it shows the lengths we’ll go and the money we’ll spend on water.

Priceless On Earth: Here on earth, there is intense and growing (but controversial) interest in defining the value of water and the monetary value of ecosystems in general. There are a wide range of opinions about what “values and valuation” imply, and whether a dollar value can be calculated for water at all.

Priceless On Earth: Here on earth, there is intense and growing (but controversial) interest in defining the value of water and the monetary value of ecosystems in general. There are a wide range of opinions about what “values and valuation” imply, and whether a dollar value can be calculated for water at all.

I have struggled with these competing ideas. On one hand, we have social and moral values, spiritual and environmental values. We value our families and living in a valley free from war and pollution. We appreciate the intrinsic value of water like we respect the intrinsic value of human life. It is inextricably linked to all we hold dear.

The indigenous Okanagan people, who have lived here for time beyond measure, are very explicit: water is alive and sacred, and essential to all other lives.

Natural Resources or Nature? On the other hand, there are the actual monetary values that are attached to water treatment, water delivery, and the things we can do with it. Someone asked me this summer, “Should farmers be able to sell water from agricultural wells to keep the farm afloat?”

Hard questions.

Calling water a “natural resource” immediately frames it as something for human use. A friend of mine was co-writing a book, and everywhere her co-author had written “water resource,” she crossed it out and wrote “water.”

Ecosystem valuation puts a dollar figure on the services provided by riparian trees and shrubs, mature forests, wetlands, and other elements of nature. These are essential services, like stabilizing stream banks and hillsides, cleaning water pollution, creating habitat for animals, generating oxygen and moderating the temperature and weather.

But it’s difficult to accurately place value on ecosystems, considering what is left in their absence. Think of a Mars-scape: no living soil, no plants, no animals or birds, just water frozen in crevices. Who wants to live there? I’d rather go swimming in Antarctica.

But it’s difficult to accurately place value on ecosystems, considering what is left in their absence. Think of a Mars-scape: no living soil, no plants, no animals or birds, just water frozen in crevices. Who wants to live there? I’d rather go swimming in Antarctica.

So far, we have been able to capitalize on redundancy (always more fish in the sea, more trees in the forest), but there are more and more cases where we’ve taken ecosystem services too much for granted – especially as the population grows.

Nature is a Tough Mother: And while we’re on the subject of money, there can be huge costs associated with water where we don’t want it: floods, landslides, and sewer back-ups. For most of our development history, building cities, roads, and bridges, we’ve assumed that the water will stay in one channel, with a predictable range of flow rates – more or less forever.

Should we calculate a negative value for water when it breaches the levies and carves a new path through Metro Vancouver or New Orleans?

Floods can also be healthy for the landscape. Farmers for millennia relied on the annual flooding of the Nile, but it’s hard to remember that when water is backing up into your basement.

Adding Value to the Invaluable: The work of the Okanagan Basin Water Board is to add value to the management of the invaluable. Resolving this contradiction is like the word problems you once loved to hate in algebra.

(a) Water itself is priceless;

(b) Ecosystems are priceless in theory, but are bought and sold anyway;

(c) Water is costly to treat and deliver, but people forget because of (a);

(d) Excess water – in our basements or spilling over roads – also has huge costs;

(e) We can add value if we reduce (c) and (d), often by relying on (b);

(f) Deciding the best approach for (e) means we sometimes have to artificially value (b);

(g) Whatever we do, we need good information and sometimes have to go after more.

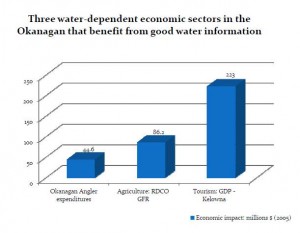

What Price Ignorance? At a recent meeting, someone asked, “But what would it cost if we didn’t do anything?” He was referring to our work collecting water data and information, and our water science studies.

What Price Ignorance? At a recent meeting, someone asked, “But what would it cost if we didn’t do anything?” He was referring to our work collecting water data and information, and our water science studies.

It’s a reasonable question, but tricky to answer. What do you compare when weighing potential future paths taken in ignorance?

Having complete knowledge of stream flows, groundwater, future climate change and the value of healthy ecosystems, would be ideal but expensive. Nonetheless, making a mistake about where to site a wastewater treatment plant (often in flood plains, but nasty when they flood), or whether to approve a golf course on groundwater (will the aquifer meet the demand?), can also be pricey for someone down the line.

We always try to go for the biggest bang for the buck: What information is most valuable? Where are the greatest potential costs and risks? How can we bring together people with joint interests to do joint projects? What gaps can we bridge, across the valley?

Einstein said, “Everything that can be counted does not necessarily count; everything that counts cannot necessarily be counted.”

Einstein said, “Everything that can be counted does not necessarily count; everything that counts cannot necessarily be counted.”

In practice, we measure what we can, and we count what we can – sometimes in litres, and sometimes in dollars. In the end, we send the new knowledge back out to the purveyors, the planners, and the policy makers so that they can make choices that protect the things we value most.

Hey Anna,

Nicely written thoughts on a difficult idea to grasp, the value of water. Part of the reason it is difficult is well described in the points you make, namely that a drop of water in one place and at one time can be very different than a drop at another place and time, and that that same drop in each place and at each time is seen differently by every person that looks at it. Kind of fitting that when each of us looks into a still pool, we see both what is in or under the water, and a reflection of ourselves. The challenge of course is how to reconcile the different personal opinions and the different situations when we have to make decisions together.

Many of the things you describe as part of the ‘value’ of water are the value of the things that water in its natural state provides for us. This is an easy to understand way of looking at water. The value of protecting a wetland is the cost we don’t have to pay to treat the water when we use it. However, this can be a dangerous approach. It is dangerous in the same way that it is dangerous to consider the value of a person as the wages they earn. By this logic, people who are retired should be dead, because this would be cheaper for society. We threw this approach out in economics quite a while back because it doesn’t take talking to too many retired people to realize that they do value their life, and would give up quite a bit to keep on living.

Another problem with using a replacement cost approach is that as technology gets better, the ecosystem becomes less valuable. Robert Costanza came up with a replacement cost value for the ecosystems of the world at something like $33 trillion per year. That would include things like having fresh water instead of needing desalinization plants. With desalinization getting cheaper, do we want that to mean that ecosystems are less valuable? That is like saying a typist’s life is worth less because we have voice recognition software.

That means we have to figure out how to find a value that reflects all the different ways that people relate to water. This means somehow combining the first people’s perspective that water is sacred and alive with the industrialist who sees it only as something she needs to clean her shop floor and cool her equipment. We can try to convince the industrialist that she should think about water as if it is alive, or we can tell the first nations peoples that they should think about water as just a resource. I don’t think anybody will like that approach. I know the first nations peoples have not been too happy with it over the last couple of hundred years. So, where we need to make choices together that involve trading water against other things, we need to come up with a value for water that fairly reflects the perspective of all the people affected and how they will be affected, to weigh against the alternative we are considering. I wish I had an easy answer to this one, but at the very least it does involve what you have nicely pointed out, good information available to everyone.

Hi John,

Thanks for your detailed comments! It shows how complex and controversial valuation and values are, once we start unpacking them.

Anna

I found both Anna’s post and John Janmaat’s thoughtful reply so encouraging. We have some strong minds and good souls considering the implications of human activity on our planet and our future. As someone who follows the many issues related to the earth’s ecology, water being uppermost I believe that our species, in particular the problem solvers, require great humility in approaching the earth’s ecology. We don’t know what we don’t know. We have a history of developing solutions that spawn new problems requiring different solutions. In retrospect it is difficult to understand how we could persist in so many destructive behaviours when the critical path from action to outcome was there to follow. The inability or perhaps unwillingness to address potential outcomes is a serious human deficit that has brought us to the brink of environmental collapse. We can’t necessarily put humpty dumpty together again. We have limitations!

Thanks, Susan. I went to a talk by Wade Davis last week, here in Kelowna. He made a point in the Q&A that there is no time for pessimism and retreat. We need to find ways to engage in positive action and dialogue with each other, even with controversial subjects like this one.

Hi Anna,

I like your blog. We see the same valuation issues and dilemma’s with Early Childhood Development (we are not providing what’s best for children, not only because we can’t measure it exactly, but also because it is very difficult to sacrifice other values (mostly monetary)). E.g. using tax dollars for a good quality child care system.

Or in the food sector. Our policies are indeed based on what we can (and do) measure. E.g. obesity, nutritional value of food etc. However we don’t address the underlying causes of why people ended up in that situation. Yet we keep telling people to eat healthy and be more active. etc. I like the quote from Einstein which you provided in the blog. I also like: Robert Chambers’: whose values count? and who counts values?

All issues important to address in new big ideas. I hope to keep on working on these myself in next couple of years.

Take care,

Menno

Hi Menno,

Your comment reminds me of a conversation I had a couple of years ago with an ethicist. At first I thought, “Applied philosophy? You can make a living doing that?” But then once he started going into detail about medical ethics, social values and costs, it made a lot of sense to have someone digging deeper into those ideas. A lot of the world runs on social consensus.

Regards,

Anna

Here’s something else that might be of interest to you all. I was just forwarded a link to a report commissioned by the EPA by CH2M Hill, called, “The Changing Value of Water to the US Economy: Implications from Five Industrial Sectors.”